Interview with Tina Cuellar, the Director of Project HEAL

After eleven years, the mental health and education nonprofit, Project HEAL, knows well the challenges facing Belizean youth.

On the frontlines of Belize’s mental health epidemic, the work of Project HEAL — an acronym standing for “hope education altering lives” — deals daily with the traumas and obstacles of children, as the nonprofit provides counseling and supplemental education for students.

But, amid the work’s intensity, Tina Cuellar, the inaugural director of Project HEAL, said she simply feels warmth and compassion.

“It always warms my heart and leans into compassion knowing the faith and the way people have trusted our program,” Cuellar said. “That for me keeps the passion going.”

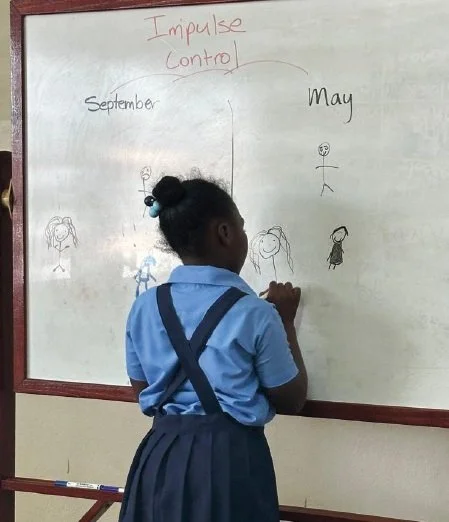

Students reflect on their emotional growth over the academic year.

The compassion and warmth described by Cuellar has become more than a guiding principle since Project HEAL started as Belize 2020’s first major project — it’s also a catalyst for growth. Over the past year, Project HEAL has launched new initiatives to ensure its various mental health services embrace those values.

The community family liaison program, introduced last school year, has quickly become one of Project HEAL’s most valuable additions, allowing the organization to take a more comprehensive approach to student mental health. Visiting homes and facilitating communication with families, the liaison helps counselors better understand a student’s home life and encourages greater family involvement in the child’s support systems.

“There were instances where you would willingly get parents to come in and communicate and do a behavioral contract,” Cuellar said. “But what we also found is that going to the homes is also really helpful. It gives us a lot of insight into more of what is going on in the child's life.”

Another such addition has been the creation of group therapy options, which have allowed counselors to meet with more students compared to individual appointments.

“We've seen that there have been patterns and issues in terms of what we call presenting problems,” Cuellar said. “In some cases it was grief, in some cases it was anger management, in some cases trauma intervention.”

Still, it has been a difficult balance for Project HEAL which has navigated a limited budget amid a growing demand from students and increased pressure on the counselors.

Project HEAL has only 20 students in their ETHeal program, an initiative for students in high school, due to not having enough funding to accept new cohorts. Meanwhile, counselors at Project HEAL have struggled with burnout due to some of the emotional intensity of their work.

Those challenges do not stop Cuellar from hoping to grow Project HEAL. She has started researching afterschool programs for more development ideas and ways to serve yong people. Visiting a Boys Hope Girls Hope in Guatemala and St. Louis’ Loyola Academy, Cuellar said she looked into bringing back an afterschool program called HEAL Academy. While that program was too expensive, Cuellar said the organization will continue to evolve and adapt as it hopes to always respond to the needs of its students.

“There's genuine investment in wanting to holistically help these children in any way that we can,” Cuellar said. “HEAL is an acronym itself. It's ‘hope education altering lives’ And that's essentially what we hope to do.”

Project HEAL’s play room.